Automotive interiors have evolved quickly. What were once simple plastic trims are now complex modules that include air ducts, sensors,

lighting, HMI parts, clips, and mixed materials. OEMs expect interiors to look seamless, feel premium, and last through heat, vibration,

and UV exposure—while still being cheap and fast to produce.

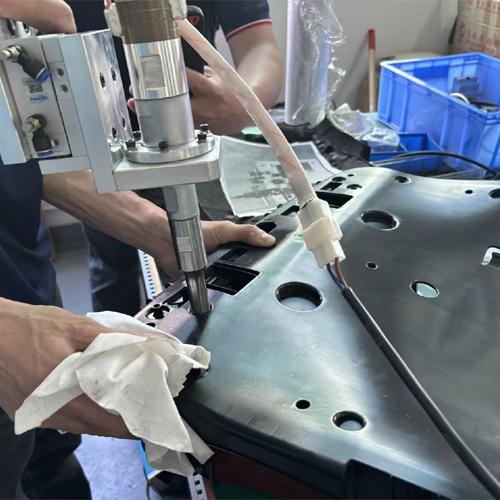

Ultrasonic welding is now a key joining method for these interior parts. It is fast, clean, and consistent, with little heat damage.

But premium interior designs—such as Class-A surfaces, thin walls, filled/recycled plastics, and built-in electronics—

also make ultrasonic welding harder than expected.

This article reviews where ultrasonic welding is used in interior accessories, why it can be difficult, and how to solve

those problems with solid design and process settings, supported by practical data.

Interior accessories include instrument panel sub-structures, center console housings, door panels, vents and HVAC ducts,

speaker grilles, lighting bezels, switch housings, and numerous clip-in or snap-fit modules. These parts are typically

thermoplastics such as ABS, PC/ABS, PP, PA, PBT, PET, and blends—with increasing use of fillers and recycled content.

Ultrasonic welding is favored because it addresses several interior production realities:

Cycle time pressure: Welding times for plastics are typically 0.2–2.0 seconds, far faster than adhesives

(often 30–180 seconds to cure) and usually faster than vibration welding for small accessories.

Cleanliness requirements:Interiors don’t tolerate adhesive squeeze-out, VOC emissions, or visible fasteners.

Ultrasonic welding needs no glue or solvent, making it cleaner and more stable for high-volume lines.

Minimal thermal distortion: Since energy is localized at the joint, cosmetic surfaces and thin ribs are less likely to warp or discolor compared to hot-plate or IR methods.

Traceable quality: Modern welders monitor energy, power, amplitude, and collapse distance, enabling inline “zero-defect” strategies that automotive programs demand.

However, success is not automatic. Interior programs fail with ultrasonic welding when part design and real production variation collide.

Ultrasonic welding is used in interiors largely for plastic-plastic joining, with some niche thin-metal welds (e.g., foil shields).

Typical interior use cases include:

Vent and HVAC duct modules: leak-controlled butt or shear joints

Console and instrument panel housings: structural joints hidden from view

Lighting / ambient-light bezels: precise joints with thin walls

Switch and sensor housings: welding around delicate internal components

Trim clip carriers and brackets: fast spot welding or staking

These parts often need a combination of high strength, good cosmetics, and stable leak performance, all under strict cost constraints.

Before discussing challenges, it helps to anchor on real parameter ranges and design baselines.

3.1 Frequencies

Common ultrasonic welding frequencies for plastics are 20 kHz and 40 kHz, with 30 kHz used when parts are small or thin-walled.

Higher frequency gives finer energy control but lower maximum weld area.

3.2 Amplitude Starting Ranges

Amplitude (peak-to-peak vibration at the horn face) is one of the most influential variables. Representative starting amplitudes for

20 kHz systems include:

ABS: ~35–45 μm

PC/ABS blends: ~45–55 μm

PC: ~50–100 μm

PP: ~70–125 μm

PA (nylon): ~90–125 μm

These are starting points; filled resins often need higher amplitude or longer energy input.

3.3 Energy Director (ED) Geometry

For interior accessories, butt joints with an energy director are the most common joint type.

The ED concentrates energy and makes weld initiation predictable.

Typical ED height guidance for amorphous plastics (ABS, PC/ABS, SAN) is 0.2–0.6 mm (0.008–0.025 in).

A 60° triangular ED is a standard baseline when the joint is not sealing-critical.

3.4 Representative Strength Windows

Well-designed ultrasonic joints can approach a large portion of base material strength. Studies on ABS and PP for automotive

applications report tensile/shear strengths in the ~18–31 MPa range depending on joint design and tuning.

For example:

ABS lap joints reached peak loads around 3.4 kN with optimized settings; optimal pressure reported near 0.13 MPa and

weld time around 1.3 s in controlled trials.

PP and PA6 joints achieved strength around 24 MPa (~75% of bulk PP strength) when parameters were optimized.

These numbers matter because interiors often require high functional strength even when weld lines are hidden.

Difficulty 1: Visible Cosmetic Marks on Class-A Surfaces

Why it happens:

Many interior parts have Class-A visible surfaces (door trim, console bezels, vents). Ultrasonic energy can “print through” as sink marks,

gloss changes, horn witness rings, or micro-scratches if vibration is not isolated from the aesthetic face.

Data signals:Excessive amplitude versus material baseline (e.g., ABS above ~45 μm without design support).

Over-weld signatures: high peak power, large collapse distance, heavy flash.

Solutions:

Move the weld line away from Class-A surfaces: Near-field welding (short distance between horn contact and joint) reduces required energy and surface stress.

Add a step joint or tongue-and-groove to hide flash:This physically shields cosmetic surfaces from molten flow.

Lower amplitude, increase weld energy in a controlled mode:Switch from time mode to energy or collapse mode to avoid overshoot.

Use hardened titanium horns with polished faces to reduce surface marking on textured trim.

Interior accessories are often molded from different resin lots, sometimes with varying filler levels or recycled content.

Small changes in melt behavior or moisture content can swing the ultrasonic energy required for a stable weld.

Data signals:

Large variation in weld energy to reach the same collapse distance.

Intermittent weak joints or brittle fractures.

Solutions:

Control moisture for hygroscopic materials (e.g., PA):Moisture variability changes viscoelastic heating and weld need.

Run energy or distance-based welding instead of fixed time: These modes absorb resin variability better.

Adopt process windows tied to material families: Use amplitude baselines per resin (ABS ~35–45 μm, PP ~70–125 μm) and

adjust weld time/energy within safe limits.

Inline signature monitoring with reject limits:Automotive plants increasingly enforce control bands on peak power, energy, and collapse to prevent “quiet drift.”

Many interior parts require tight assembly gaps and precise snaps. Excess molten polymer (flash) can interfere with fit,

squeak/noise performance, or later clip engagement.

Data signals:

Flash visible around joint perimeter.

Collapse distance exceeding spec.

Burn marks in localized over-heat areas.

Solutions:

Add flash traps: Small cavities adjacent to the ED capture molten flow without affecting outer geometry.

Reduce amplitude or weld time if flash is energy-driven: Over-weld is a parameter problem more often than a material problem.

Increase fixture stiffness and part support: If the lower part “breathes” outward under pressure, you will get uncontrolled squeeze-out.

Interior accessories often have complex shapes with multiple clip points and thin walls. If fixturing or molded tolerance allows

misalignment, ultrasonic energy distributes unevenly and weld area becomes non-uniform.

Data signals:

One-sided flash.

Power spikes early in the cycle.

Reduced welded area, large strength scatter. Misalignment is a documented driver of strength loss.

Solutions:

Add robust alignment bosses/steps: Don’t rely on “operator feel.”

Upgrade nest design to constrain all degrees of freedom:Particularly important for vents and ducts.

Upgrade nest design to constrain all degrees of freedom:

Use a compliant energy director strategy when alignment variation is unavoidable: Research shows ED compliance reduces misalignment

sensitivity and improves welded area uniformity.

Interior designers push towards thin, lightweight plastics: But thin walls flex, absorbing vibration before it reaches the weld line. The result is long weld times, overheating in random locations, or no weld at all.

Data signals:

Needing unexpectedly high amplitude (e.g., ABS beyond 45–55 μm).

Slow temperature rise at the interface.

“Cold welds” with low collapse. twi-global.com+1

Solutions:

Increase local stiffness near the joint using ribs that terminate before the weld line.

Move to a higher-frequency system (30–40 kHz) for very thin or small parts.

Use shear joints for structural strength when butt joints struggle. Shear joints can reach ~90–95%

shear efficiency relative to base material under good design.

Why it happens?

Fillers improve stiffness and heat resistance, but they also reduce acoustic transmission and change melt flow.

Interiors use filled PP and PA heavily for durability. These materials typically need more energy and cleaner joint geometry.

Data signals:

Higher required amplitude/time to reach target collapse.

Sporadic voids or weak interfacial fusion.

Solutions:

Adjust ED geometry: For some filled systems, semi-circular or modified EDs perform better than standard sharp triangles.

Run DOE to set a stable window: Amplitude is usually the dominant factor for strength; optimize amplitude-pressure-time together.

Prefer energy/distance mode: Filled resin variability is much better handled by closed-loop stop criteria.

Interiors increasingly integrate lighting boards, capacitive sensors, or chrome/film inserts. These can be damaged by

excessive vibration or localized overheating.

Data signals:

Early-cycle power spikes.

Insert deformation or delamination.

Post-weld functional failures.

Solutions:

Isolate energy with careful horn contact design so vibration path does not cross the insert.

Lower amplitude and increase hold time slightly to let the melt form without aggressive energy.

Use near-field welding and precisely machined nests to keep energy localized.

For a common interior accessory made from ABS or PC-ABS with a triangular ED (0.2–0.6 mm) and a butt joint,

a practical starting window on a 20 kHz system is often:

Amplitude: 35–55 μm baseline (depending on blend and fillers)

Weld time: 0.4–1.5 s (shorter for near-field, longer for thicker sections)

Pressure: around 0.1–0.2 MPa range is common in ABS optimization work MDPI

Hold time: 0.2–0.8 s to allow solidification without throughput loss.

You will still need a structured DOE, but these baselines prevent the most common “first-article failures.”

Automotive interiors demand high cosmetics and long-term durability, so relying only on “pass/fail visual checks” is not enough. A robust approach is:

Real-time weld signature limits:

Peak power window

Total energy window

Collapse distance window

Time window as a secondary lock

Any weld outside limits is auto-rejected.

Statistical strength validation:

Peel or lap-shear tests on samples per shift

Target strengths aligned with program spec (often 70–95% of base material depending on joint type).

Leak tests for ducts/vents:

Pressure decay or airflow-based checks after welding.

Duct integrity is one reason ultrasonic welding dominates small HVAC interior modules.

Ultrasonic welding is a highly mature and economically powerful process for automotive interior built-in accessories.

Its speed (0.2–2.0 s weld cycles), cleanliness, low thermal impact, and data-rich monitoring align perfectly with interior production needs.

But the interiors domain is also one of the hardest environments for ultrasonic welding because it combines Class-A cosmetic requirements,

thin walls, filled resins, tight tolerances, and embedded electronics.

The good news is that these challenges are solvable—primarily through correct joint design (energy directors around 0.2–0.6 mm for ABS-family parts),

material-appropriate amplitude baselines (ABS ~35–45 μm; PP ~70–125 μm), strong fixturing, and closed-loop energy or collapse-based control.

With those fundamentals in place, interior weld joints can reach strength levels on the order of ~18–31 MPa in optimized cases, often approaching

the functional strength needed for long-life automotive service

Phone: +86-15989541416

E-mail: michael@sztimeast.com

Whatsapp:+86-15989541416

Add: 3/F, Building 5,Huixin Intelligent Industrial Park, Xinhu, Guangming, Shenzhen,China 518107